Code

# Import packages

import ee

import geemap

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import json

from itertools import chain

import osJanuary 10, 2023

Jessica French jfrench@bren.ucsb.edu

Javier Patrón jpatron@bren.ucsb.edu

Pol Carbó Mestre pcarbomestre@bren.ucsb.edu

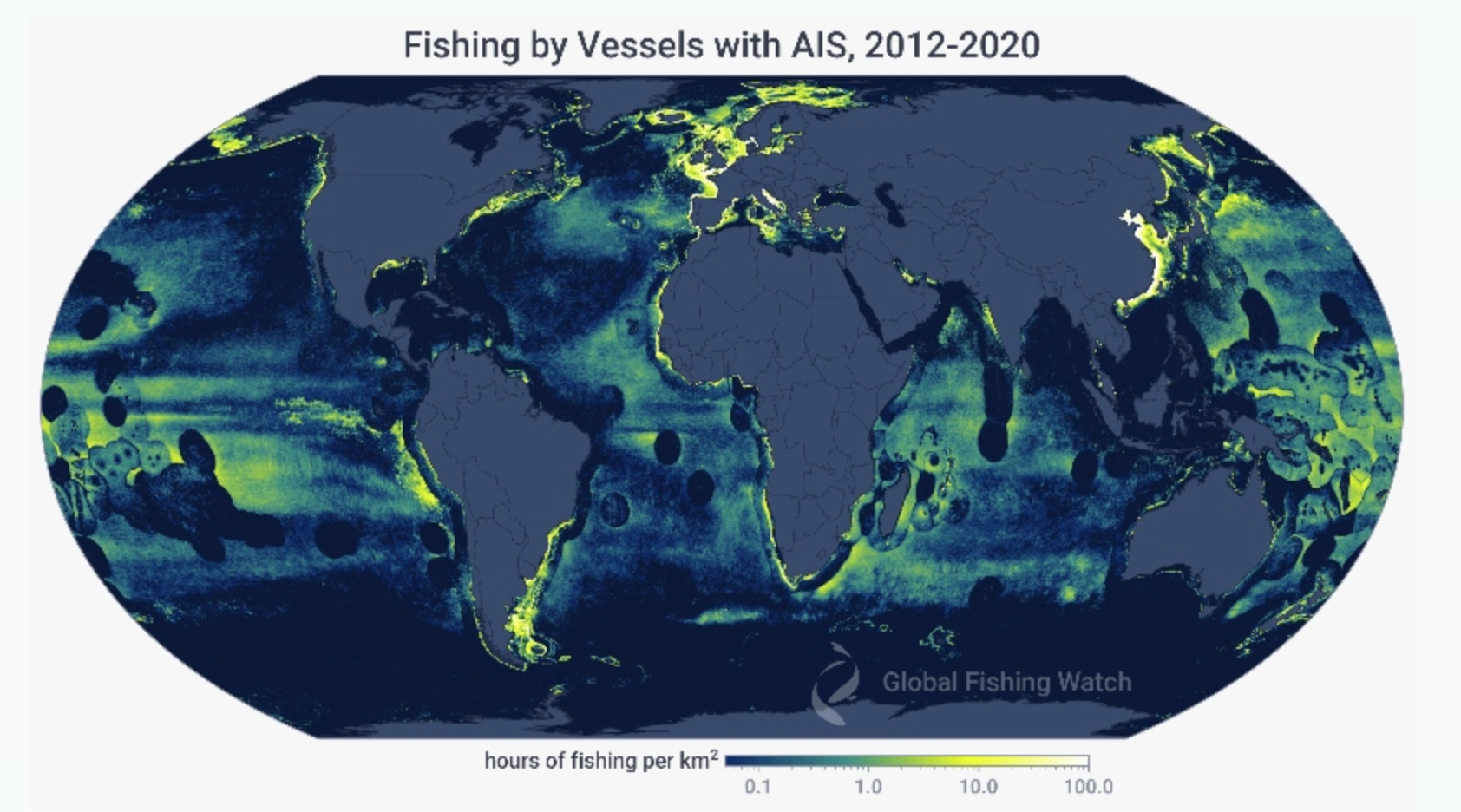

The purpose of this notebook is to explore Global Fishing Watch’s dataset showing daily fishing effort as inferred fishing hours daily. This notebook will show how to read in the dataset, visualize the data using google earth engine, and give an overview of how the data can be used to explore differences in fishing effort within and outside Peru’s EEZ and how fishing effort is impacted by El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events.

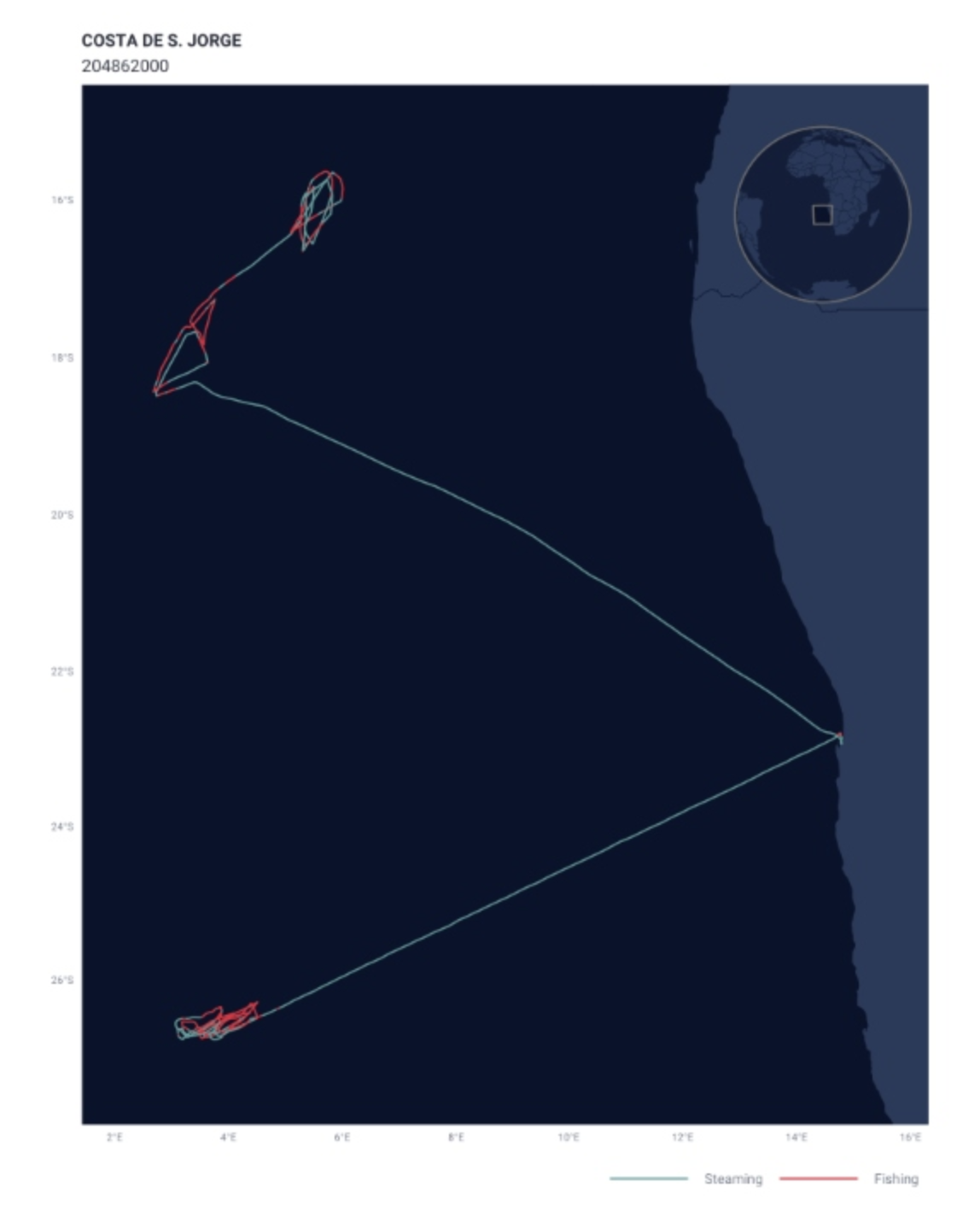

The Global Fishing Watch (GFW) provides an open platform to access Automatic Identification System (AIS) data from commercial fishing activities. The AIS is a tracking system that uses transceivers on ships to broadcast vessel information such as unique identification, position, course, and speed. AIS is integrated into all classes of vessels as a collision avoidance tool. However, the GFW collects and processes raw AIS data related to fishing activities to improve records and assign additional information, such as the distance from shore, depth, etc. Then, with the use of machine learning models, they characterize vessels and fishing activities, which constitute some of the products available in their API.

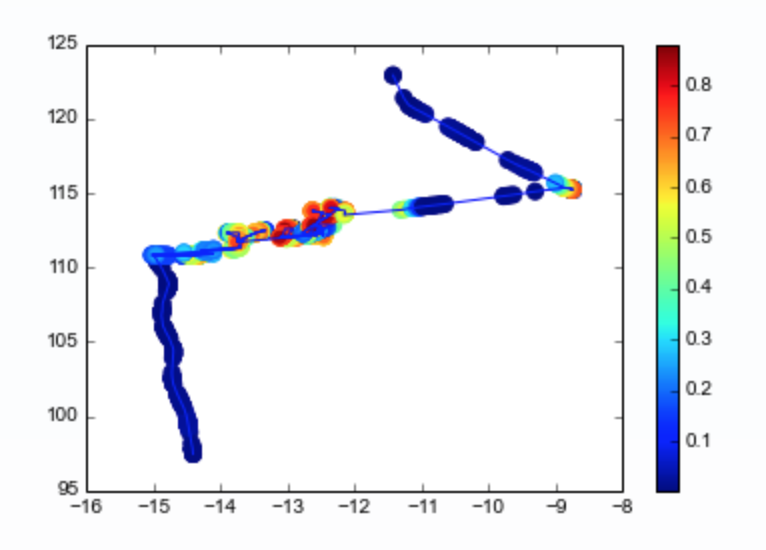

One of the most interesting products that the GFW API offers is estimates of fishing effort derived from AIS data. GFW uses machine learning models to classify fishing vessels and predict when they are fishing. First, they identify fishing vessels in the AIS system. Then the vessel is characterized using the best available information and their fleet registry data combined with a characterization model trained on 45,441 marine vessels (both fishing and non-fishing) matched to official fleet registries. Then, GFW estimates the vessel’s fishing time and location based on its movement patterns. To do so, a fishing detection model was trained on AIS data from 503 ships and identified fishing activity with >90% accuracy. The model predicts a score for every AIS position in their database to distinguish fishing positions from non-fishing positions (i.e., navigation time). When the model identifies fishing activity, the time associated with that AIS position is registered as apparent fishing activity. More details about the model can be found on the following GitHub repository (link).

Once the fishing vessels are identified and their AIS positions have been assigned as fishing positions, the apparent fishing effort can be calculated for any area by summarizing the fishing hours for all fishing vessels in that area. The resulting maps of apparent fishing effort are created by rasterizing all AIS positions into a grid and calculating the total fishing activity in each grid cell. For the present project we will access this type processed data.

Pre-processed AIS data can be accessed from their R package “gfwr” or downloaded from their website as .cvs files. For this project, we will use some of their existing products related to fishing effort. The data can be accessed from Google Big Query in a less processed format and through Google Earth Engine (GEE) for two data subproducts daily fishing hours and daily vessel hours. For accessibility reasons, we will focus on the GEE data related to fishing hours.

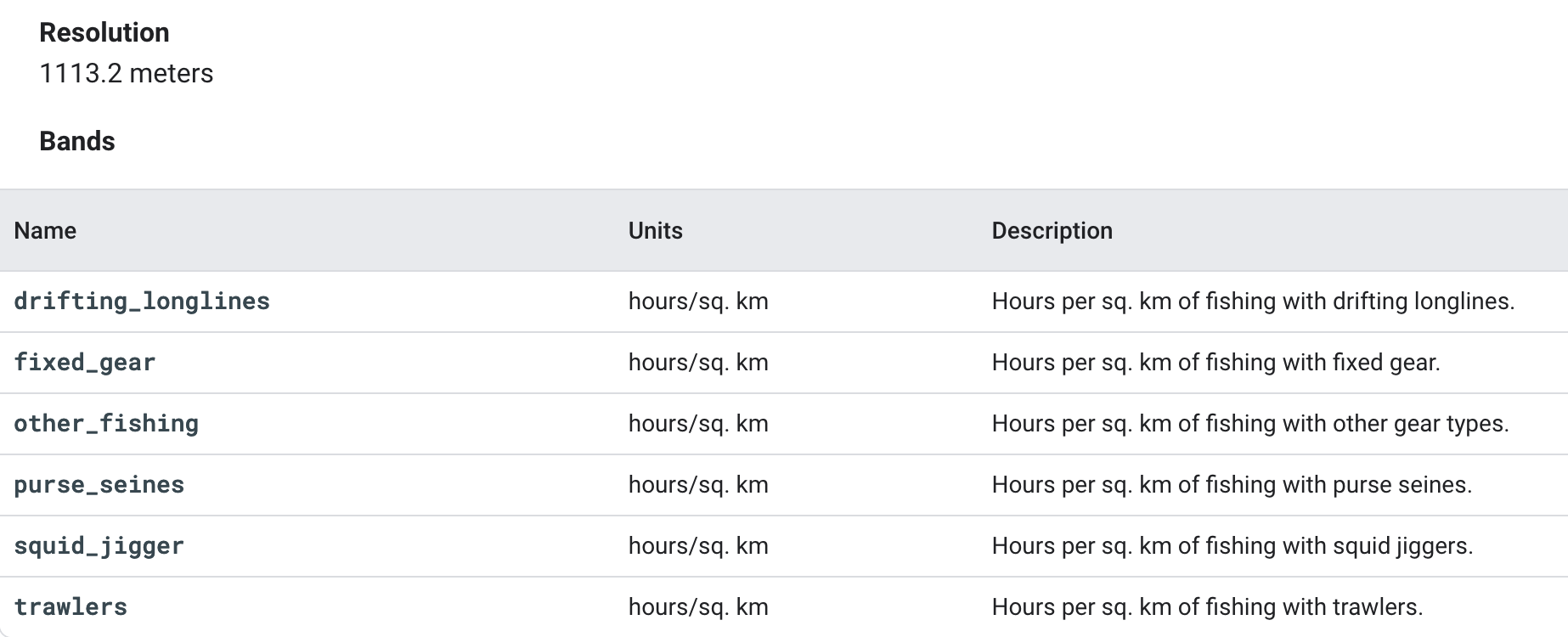

Each image in the collection contains daily rasters of fishing effort measured in hours of inferred fishing activity per square kilometer. Data is available for a given flag state and day, over a 5 years period (2012-2017), where each band represent a fishing gear type. The following figure summarizes the image resolution and the available bands.

The data used belongs to the first global assessment of commercial fishing activity, published in Science by GFW (2018).

This section will show you how to read in the data and define some of the mapping parameters we will use in later sections.

Load in necessary packages.

Authenticate and initialize google earth engine.

If the above command does not work run the following code in the terminal. earthengine authenticate --auth_mode=notebook

Read in the data from google earth engine and filter metadata to include all countries.

# Read in the data on fishing hours from google earth engine

dataset = ee.ImageCollection('GFW/GFF/V1/fishing_hours')

# Filter by "WLD" to get all global fishing vessel hours. This includes all countries in the dataset.

fishing_effort_ImgCollection = dataset.filterMetadata('country', 'equals', 'WLD')

# SRTM data to use for background in the gif.

SRTM=ee.Image("USGS/GTOPO30")We define two areas of interest (AOI) for the time series analysis. The first one relative to the EEZ of Peru stored data/eez_peru/geojson/eez_peru.geojson. The second AOI is a square area comprizing the EEZ and the neigboring waters in the west. We chose to focus on the area of Peru’s coast that includes two of the largest fishing ports, Paita and Callao.

# Read in EEZ geometry of Peru

f = open('/Users/jfrench/Documents/Website/jessicafrench.github.io/blog_posts/2023-01-09-peru-fisheries/data/eez_peru/geojson/eez_peru.geojson')

geojson = json.load(f)

coords = geojson["features"][0]["geometry"]["coordinates"]

## The resulting List from the geojson file has an extra bracket that we have to remove to be read in as a polygon

aoi_1 = ee.Geometry.Polygon([i for i in chain.from_iterable(coords)])# Defining new AOI including areas beyond the EEZ

geojson = {

"type": "FeatureCollection",

"features": [

{

"type": "Feature",

"properties": {},

"geometry": {

"coordinates": [

[

[

-89.8703470212856,

-2.9010789371311176

],

[

-89.8703470212856,

-19.936548732128458

],

[

-70.081492068508,

-19.936548732128458

],

[

-70.081492068508,

-2.9010789371311176

],

[

-89.8703470212856,

-2.9010789371311176

]

]

],

"type": "Polygon"

}

}

]

}

coords = geojson["features"][0]["geometry"]["coordinates"]

aoi_2 = ee.Geometry.Polygon(coords)Define visualization parameters.

We can look at the metadata and bands in a couple different ways. The code below is a little overwhelming and diffficult to search through.

{'type': 'Image', 'bands': [{'id': 'drifting_longlines', 'data_type': {'type': 'PixelType', 'precision': 'float'}, 'dimensions': [36000, 16500], 'crs': 'EPSG:4326', 'crs_transform': [0.01, 0, -180, 0, -0.01, 85]}, {'id': 'fixed_gear', 'data_type': {'type': 'PixelType', 'precision': 'float'}, 'dimensions': [36000, 16500], 'crs': 'EPSG:4326', 'crs_transform': [0.01, 0, -180, 0, -0.01, 85]}, {'id': 'other_fishing', 'data_type': {'type': 'PixelType', 'precision': 'float'}, 'dimensions': [36000, 16500], 'crs': 'EPSG:4326', 'crs_transform': [0.01, 0, -180, 0, -0.01, 85]}, {'id': 'purse_seines', 'data_type': {'type': 'PixelType', 'precision': 'float'}, 'dimensions': [36000, 16500], 'crs': 'EPSG:4326', 'crs_transform': [0.01, 0, -180, 0, -0.01, 85]}, {'id': 'squid_jigger', 'data_type': {'type': 'PixelType', 'precision': 'float'}, 'dimensions': [36000, 16500], 'crs': 'EPSG:4326', 'crs_transform': [0.01, 0, -180, 0, -0.01, 85]}, {'id': 'trawlers', 'data_type': {'type': 'PixelType', 'precision': 'float'}, 'dimensions': [36000, 16500], 'crs': 'EPSG:4326', 'crs_transform': [0.01, 0, -180, 0, -0.01, 85]}], 'version': 1518594814620050.0, 'id': 'GFW/GFF/V1/fishing_hours/ARG-20120101', 'properties': {'system:time_start': 1325376000000, 'country': 'ARG', 'system:footprint': {'type': 'LinearRing', 'coordinates': [[-180, -90], [180, -90], [180, 90], [-180, 90], [-180, -90]]}, 'system:time_end': 1325462400000, 'system:asset_size': 731, 'system:index': 'ARG-20120101'}}This code allows you to see only the band names and numbers in a more readable format.

0 drifting_longlines

1 fixed_gear

2 other_fishing

3 purse_seines

4 squid_jigger

5 trawlers

NoneTo read on the metadata we will first create an object image from the collection and index their properties. To built this first image we will create and use simple methods over the original dataset of GEE.

# Creating an image with some filters on time and space

fishing_image = dataset \

.filterBounds(aoi_2) \

.first()

# See image properties with their names and values

fishing_props = geemap.image_props(fishing_image)

fishing_props.getInfo()

# Index by country

country = fishing_props.get('country')

print('Country:', country.getInfo())

#Represent the image properties with propertyNames()

properties = fishing_image.propertyNames()

print('Metadata properties:' , properties.getInfo())Country: ARGMetadata properties: ['system:time_start', 'country', 'system:footprint', 'system:time_end', 'system:version', 'system:id', 'system:asset_size', 'system:index', 'system:bands', 'system:band_names']The GFW website allows us to access individual datasets of AIS-based fishing effort and vessel presence. These datasets are provided in daily .csv file format and include the same data that is available through the GFW’s Google Earth Engine (GEE) API. By examining these files, we can gain insight into the GEE API metadata, such as the number of fishing hours per cell and day, the fishing state flag, and the type of gear used. This information can help us understand how the data is structured on the GEE fishing hours dataset.

| date | cell_ll_lat | cell_ll_lon | flag | geartype | hours | fishing_hours | mmsi_present | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2016-01-01 | -4.00 | -144.82 | USA | fishing | 0.2005 | 0.0 | 1 |

| 1 | 2016-01-01 | -4.25 | -144.92 | USA | fishing | 0.0750 | 0.0 | 1 |

| 2 | 2016-01-01 | 5.25 | -138.54 | USA | fishing | 1.4925 | 0.0 | 1 |

| 3 | 2016-01-01 | -5.75 | -145.45 | USA | fishing | 0.0500 | 0.0 | 1 |

| 4 | 2016-01-01 | -6.50 | -164.41 | USA | fishing | 0.0333 | 0.0 | 1 |

From that file, we can group, count, and sort the data to see which countries and gear types are most highly represented for that day.

CHN 39022

TWN 6297

RUS 6164

JPN 6130

USA 5213

Name: flag, dtype: int64

trawlers 38067

drifting_longlines 21721

fishing 13557

set_longlines 6244

tuna_purse_seines 3758

Name: geartype, dtype: int64Peru is the second largest producer of wild caught sea food in the world landing 5,658,917 tonnes in 2020 (FAO, 2022). The marine fishing sector is responsible for 232,000 jobs and $3.2 billion in GDP as of 2005 (Christensen et al., 2014). Peruvian fishers were some of the first people to recognize El Niño events through their impact on fisheries (El Niño | National Geographic Society). El Niño Southern Oscillation causes warmer ocean temperatures and a reduction in upwelling, reducing the number of anchoveta and fisheries production.

Our case study focuses on using Global Fishing Watch (GFW) data on fishing hours to explore fishing activities inside and outside of Peru’s economic exclusive zone (EEZ). The Peruvian fisheries serve as a valuable example of how international law, including the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, enables developing countries to retain control over their marine resources and maintain food sovereignty. This is especially critical as foreign fleets from across the globe often take advantage of the rich fishing resources and high productivity of Peruvian waters, which extend beyond the boundaries of the EEZ. By studying the data on fishing hours, we can gain a better understanding of the overall health and sustainability of the Peruvian fisheries. This information can provide valuable insights into the importance of the EEZ for Peru and how it helps to protect the country’s marine resources from being exploited by foreign fleets.

In addition to providing insights into the importance of the EEZ, our analysis will also investigate whether trends in fishing efforts can be used as a proxy to evaluate the impacts of El Niño events on the Peruvian fisheries. Although this constitutes a secondary aspect of our study, we will comment on the fishing fluctuations and whether they may be influenced by the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). El Niño events can be identified using the Ocean Niño Index (ONI), which is a 3-month running mean of ERSST.v5 sea surface temperature anomalies in the Niño 3.4 region (between 5 degrees North and South of the equator and between 120 and 170 degrees West). For this study, we will focus on the 2015 El Niño event and compare it to the data from the previous year. More information is available here

This Visualization map allows us to understand the significance of Exclusive Economic Zones, particularly in the case of Peru where the fishing industry contributes significantly to the country’s GDP. By using this map, we can compare the total fishing hours within and outside of Peru’s EEZ without considering the flag or gear type. This information is crucial for understanding the impact Peru’s EEZ for managing and regulating this sector.

# Global fishing effort:

## Aggregate 2016 collection to single image of global fishing effort

effort_all = fishing_effort_ImgCollection.sum()

## Sum bands to get total effort across gear types

effort_all = effort_all.reduce(ee.Reducer.sum())

## Mask out pixels with no effort

effort_all = effort_all.mask(effort_all.gt(0))# Fishing effort in Peru's EEZ

effort_EEZ = fishing_effort_ImgCollection.filterBounds(aoi_1).map(lambda image: image.clip(aoi_1))

## Aggregate 2016 collection to single image of global fishing effort

effort_EZZ = effort_EEZ.sum()

## Sum bands to get total effort across gear types

effort_EZZ = effort_EZZ.reduce(ee.Reducer.sum())

## Mask out pixels with no effort

effort_EZZ = effort_EZZ.mask(effort_EZZ.gt(0))# Comparing the two maps

left_layer = geemap.ee_tile_layer(effort_EZZ, trawlersVis, name = "All 2016", opacity = 0.9)

right_layer = geemap.ee_tile_layer(effort_all, trawlersVis, name = "Effort EZZ", opacity = 0.9)

map_comparison = geemap.Map(center = [-15, -83],zoom = 5)

map_comparison.centerObject(aoi_1, 5)

map_comparison.setOptions("HYBRID")

map_comparison.addLayer(aoi_1, {"color": "white", "width": 1.5}, "EEZ of Perú");

map_comparison.split_map(left_layer, right_layer)

map_comparisonAnother aspect worth exploring is the evolution of the fishing effort across the years. The following code allows us to create an animated image of fishing activity in front of Peru. To do this, we will first aggregate the daily data into monthly fishing hour estimates. Then, we will sum up all band values to obtain information about total fishing. With the resulting images, we will create a .gif to visualize the temporal and spatial evolution of the fisheries.

# monthly sum of fishing effort

def monthly_Sum (collection, years, months):

effort_sum = []

for year in years:

for month in months:

Monthly_sum = collection.filter(ee.Filter.calendarRange(year, year, 'year')) \

.filter(ee.Filter.calendarRange(month, month, 'month')) \

.sum() \

.reduce(ee.Reducer.sum()) \

.set('system:time_start',{'month': month, 'year': year})

Monthly_sum = Monthly_sum.mask(Monthly_sum.gt(0))

Monthly_sum = SRTM.blend(Monthly_sum)

effort_sum.append (Monthly_sum)

return ee.ImageCollection.fromImages(effort_sum)

# list of images

def monthly_images (collection, years, months):

effort_images = []

for year in years:

for month in months:

Monthly_sum = collection.filter(ee.Filter.calendarRange(year, year, 'year')) \

.filter(ee.Filter.calendarRange(month, month, 'month')) \

.sum() \

.reduce(ee.Reducer.sum()) \

.set('system:time_start',{'month': month, 'year': year})

effort_images.append (Monthly_sum)

return effort_images# Create an image collection of fishing effort where each image is a sum of the fishing effort for that month.

effort_collection = monthly_Sum(fishing_effort_ImgCollection, years, months)

# Creates a list of the images from the image collection.

effort_list = monthly_images(fishing_effort_ImgCollection, years, months)

len(effort_list)60# Creates an empty list to be populated with month and year of images.

date_list = []

# Populates the date_list with the month and year of each image. This will be used to annotate the gif with a time stamp.

for i in effort_list:

date = i.get('system:time_start').getInfo()

date_list.append(date)

len(date_list)60Generating URL...Downloading GIF image from https://earthengine.googleapis.com/v1alpha/projects/earthengine-legacy/videoThumbnails/74d674bad7b2624f834ab73885feff9d-cea3953b2dfde00d20936cc86f973fb1:getPixels

Please wait ...The GIF image has been saved to: /Users/jfrench/Documents/Website/jessicafrench.github.io/blog_posts/2023-01-09-peru-fisheries/img/monthly_fishing.gifIn the previous .gif, we can observe a seasonal pattern where fishing grounds migrate from the north to the south along the coast and the EEZ borders, with months experiencing minimal activity. However, one limitation of the image the difficulty to discern trend changes across years, making it challenging to determine if ENSO events may be diminishing fishing activity.

In order to further analyze the observed fishing differences between the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and the region immediately next to it, we will extract temporal series of total fishing hours inside and outside the EEZ. This will provide us with a quantifiable measure to compare the fishing efforts in these two areas. Additionally, the temporal series may enable us to identify any patterns or trends in fishing effort that may be influenced by the 2015 El Niño event.

Since the GEE dataset exceeds the allowed extraction size, we have created a function that calls for the data of interest in order to work with it in pandas. The following function allow us to agregate all daily fishing hours values per month. With it we get first a dataset with monthly data instead of daily. Once we have temporarilly aggregated the data, we apply a reducer to sum up all fishing gears in one band and get a unique value representing the total fishing hours.

# Loop ranges already defined for the gif.

# Function to extract data of interest:

## .sum() Aggregates collections to single monthly image of global fishing effort

## .reduce(ee.Reducer.sum()) Sum bands to get total effort across all gear types

def monthly_Sum (collection, years, months):

effort_sum = []

for year in years:

for month in months:

Monthly_sum = collection.filter(ee.Filter.calendarRange(year, year, 'year')) \

.filter(ee.Filter.calendarRange(month, month, 'month')) \

.sum() \

.reduce(ee.Reducer.sum()) \

.set('year', year).set('system:time_start', ee.Date.fromYMD(year, 1, 1))\

.set('month', month).set('system:time_start', ee.Date.fromYMD(year, month, 1).millis())

effort_sum.append (Monthly_sum)

return ee.ImageCollection.fromImages(effort_sum)ee.imagecollection.ImageCollectionOur updated image collection now includes monthly fishing data for all gears combined. In order to effectively analyze the time series of this data, we will need to design a new function that allows us to summarize the information within our designated areas of interest (AOIs). This function will take the AOI as a parameter, enabling us to conduct time series analysis on each AOI individually. The upcoming sections will focus on conducting time series analysis for each AOI.

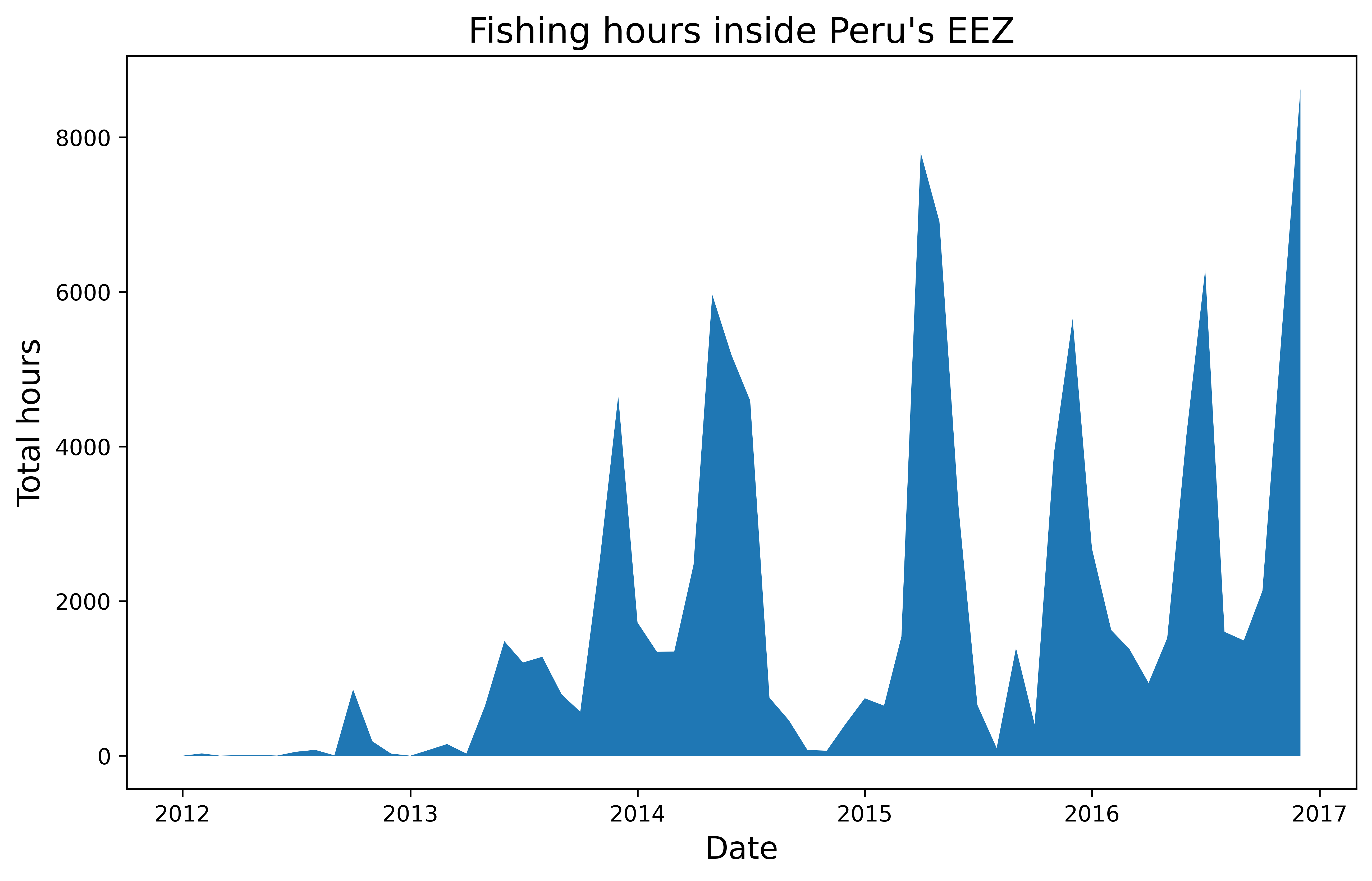

The following time serie correspond to the fishing data contained inside the EEZ. previously saved as aoi_1.

# Function to summarize fishing monthly data:

## Extracting all image values in the collection by the AOI relative to the EEZ

def aoi_sum(img):

sum = img.reduceRegion(reducer=ee.Reducer.sum(), geometry=aoi_1, # EEZ area of interest

scale=1113.2) # Resolution of the GFW product

return img.set('time', img.date().millis()).set('sum',sum)

aoi_reduced_imgs = byMonth.map(aoi_sum)

nested_list = aoi_reduced_imgs.reduceColumns(ee.Reducer.toList(2), ['time','sum']).values().get(0)# Converting GEE data to Pandas and rearranging it for its representation

df = pd.DataFrame(nested_list.getInfo(), columns=['time','sum'])

df['sum'] = df['sum'].apply(lambda x: x.get('sum'))

df.rename(columns = {'sum':'total_fishing_hours'}, inplace = True)

df["id"] = df.index

first_column = df.pop('id')

df.insert(0, 'id', first_column)

# Setting time format for representation purposes

df['datetime'] = pd.to_datetime(df['time'], unit='ms')

df['datetime'] = pd.to_datetime(df['datetime'],format="%Y%m%d")

#df.head()plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6), dpi=300) # create a new figure, set size and resolution (dpi)

plt.fill_between(df['datetime'],df['total_fishing_hours']) # add data to the plot

plt.title("Fishing hours inside Peru's EEZ", fontsize=16)

plt.xlabel('Date', fontsize=14)

plt.ylabel('Total hours', fontsize=14)Text(0, 0.5, 'Total hours')

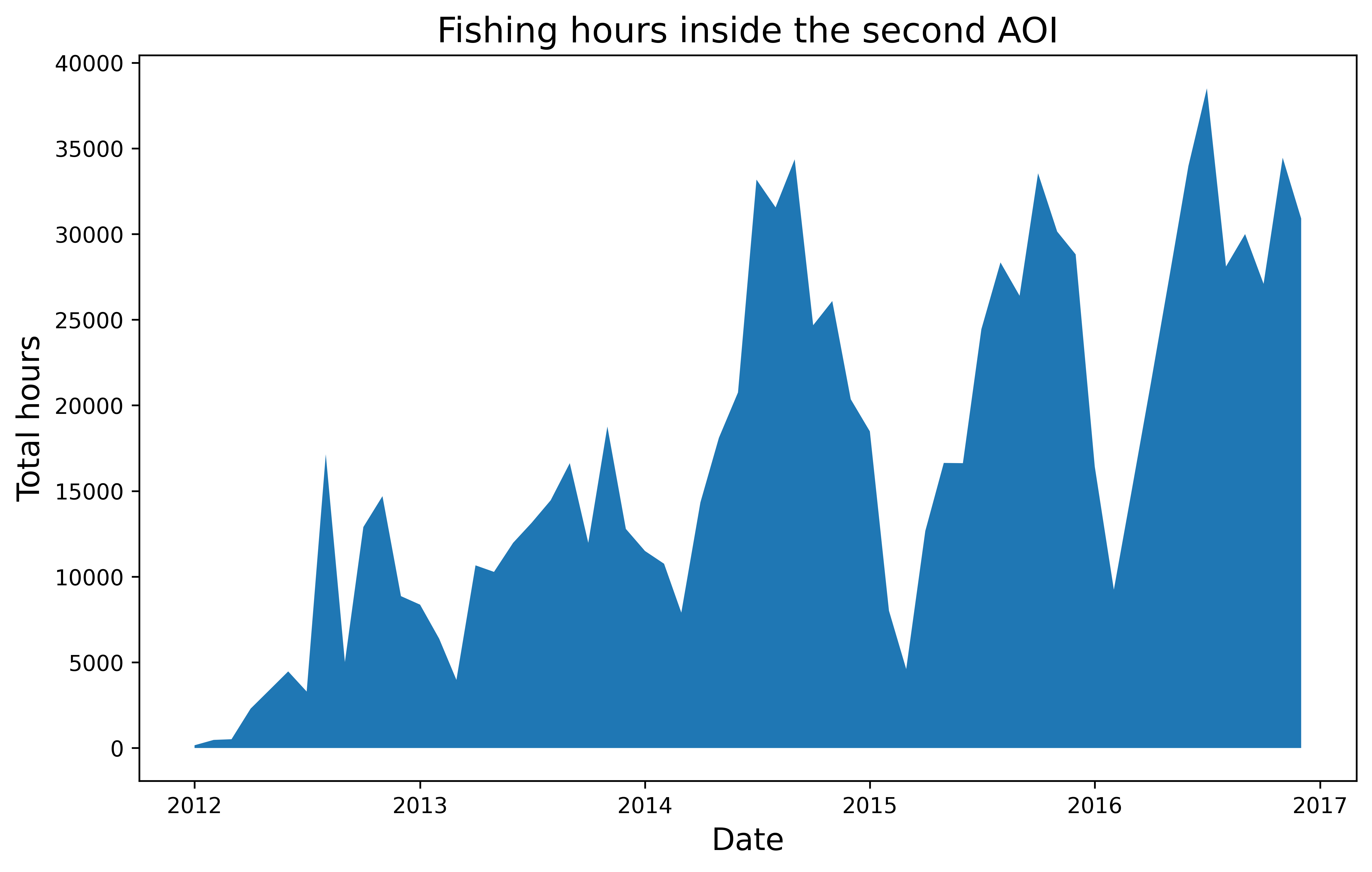

To characterize the fishing activity outside of the EEZ, we need to define a new area of interest. In this case, we will focus on a square region with the same latitude boundaries as the EEZ but extending towards the west in longitud (aoi_2). The first step is to quantify the number of fishing hours over that region. Then we will substract the EEZ fishing hours previously calculated from it to graphically compare effort from inside and outside.

The map below shows the new area of interest and the data across a the 5-year time period that will be included in the time series analysis.

# Fishing effort in Peru's EEZ

effort_AOI2 = fishing_effort_ImgCollection.filterBounds(aoi_2).map(lambda image: image.clip(aoi_2))

## Aggregate 2016 collection to single image of global fishing effort

effort_AOI2 = effort_AOI2.sum()

## Sum bands to get total effort across gear types

effort_AOI2 = effort_AOI2.reduce(ee.Reducer.sum())

## Mask out pixels with no effort

effort_AOI2 = effort_AOI2.mask(effort_AOI2.gt(0))

# Add the total fishing effort layer

Map = geemap.Map(zoom = 2)

Map.centerObject(aoi_2, 5)

Map.setOptions('HYBRID');

Map.addLayer(aoi_2, {'color': 'white','width': 1.5}, "Sampling area");

Map.addLayer(effort_AOI2,trawlersVis);

Map# Function to summarize fishing monthly data inside and outside the EEZ

def aoi_sum(img):

sum = img.reduceRegion(reducer=ee.Reducer.sum(), geometry=aoi_2,

scale=1113.2)

return img.set('time', img.date().millis()).set('sum',sum)

aoi_reduced_imgs = byMonth.map(aoi_sum)

nested_list = aoi_reduced_imgs.reduceColumns(ee.Reducer.toList(2), ['time','sum']).values().get(0)

# Converting GEE data to Pandas and rearranging it for its representation

df2 = pd.DataFrame(nested_list.getInfo(), columns=['time','sum'])

df2['sum'] = df2['sum'].apply(lambda x: x.get('sum'))

df2.rename(columns = {'sum':'total_fishing_hours'}, inplace = True)

df2["id"] = df2.index

first_column = df2.pop('id')

df2.insert(0, 'id', first_column)

df2['datetime'] = pd.to_datetime(df2['time'], unit='ms')

df2['datetime'] = pd.to_datetime(df2['datetime'],format="%Y%m%d")

# Ploting time series

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6), dpi=300)

plt.fill_between(df2['datetime'],df2['total_fishing_hours'])

plt.title("Fishing hours inside the second AOI", fontsize=16)

plt.xlabel('Date', fontsize=14)

plt.ylabel('Total hours', fontsize=14)Text(0, 0.5, 'Total hours')

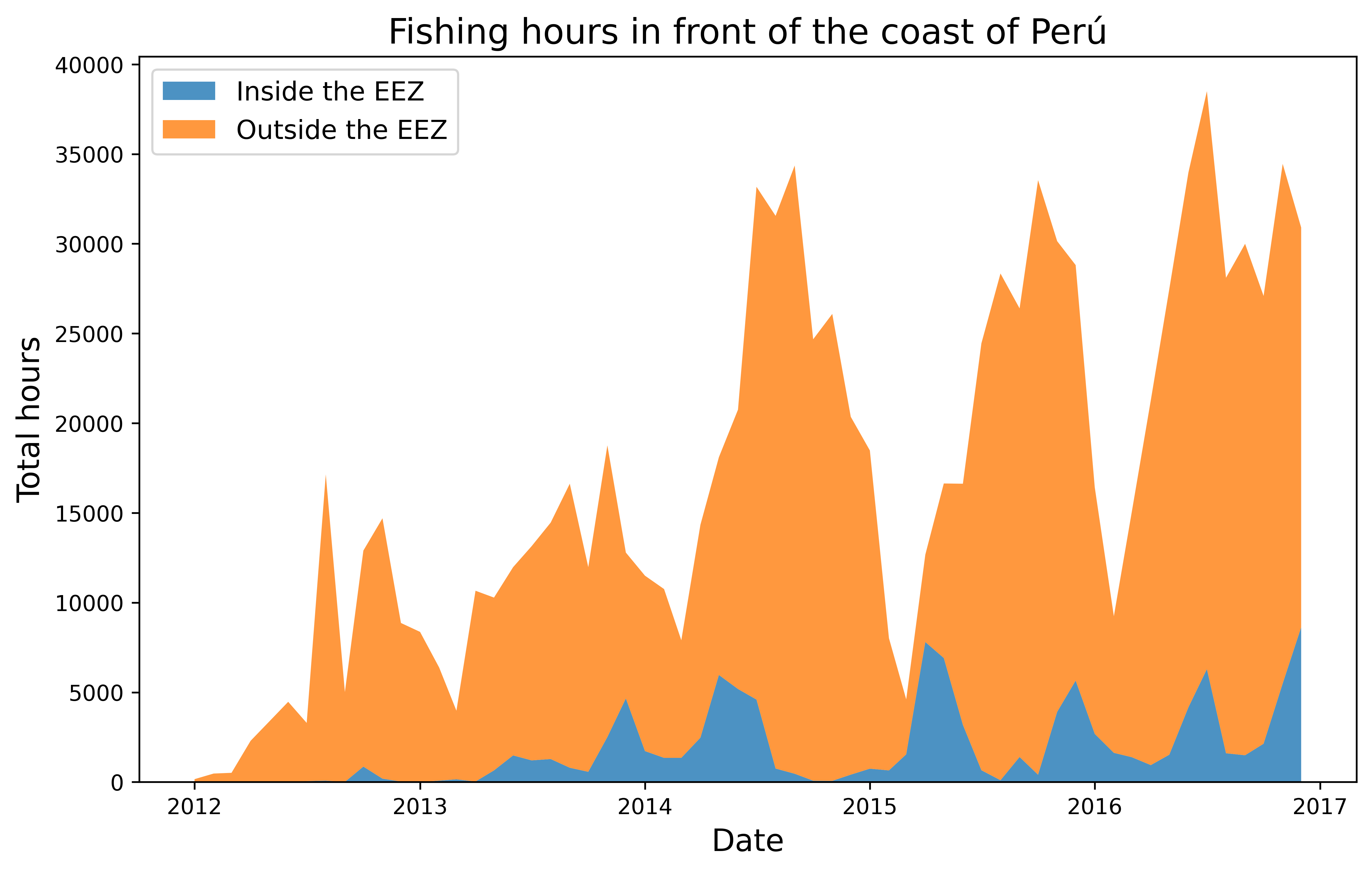

To compare fishing efforts within and outside, we can subtract the total fishing hours from the previous dataframes. This will give us the actual fishing effort outside the EEZ, which we can then represent alongside fishing within the EEZ in an area chart for easy visualization and comparison.

# Combining both df

df["total_fishing_hours_outside"] = abs(df["total_fishing_hours"] - df2["total_fishing_hours"])

df.rename(columns = {'total_fishing_hours':'total_fishing_hours_inside'}, inplace = True)

total_fishing_df = df[['id', 'time', 'datetime','total_fishing_hours_inside','total_fishing_hours_outside']]

total_fishing_df.head()| id | time | datetime | total_fishing_hours_inside | total_fishing_hours_outside | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1325376000000 | 2012-01-01 | 0.000000 | 160.185273 |

| 1 | 1 | 1328054400000 | 2012-02-01 | 29.597059 | 442.994487 |

| 2 | 2 | 1330560000000 | 2012-03-01 | 0.683282 | 512.164755 |

| 3 | 3 | 1333238400000 | 2012-04-01 | 7.479013 | 2290.269927 |

| 4 | 4 | 1335830400000 | 2012-05-01 | 11.036600 | 3353.737642 |

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6), dpi=300)

plt.stackplot(total_fishing_df['datetime'],

[total_fishing_df['total_fishing_hours_inside'], total_fishing_df['total_fishing_hours_outside']],

labels=['Inside the EEZ', 'Outside the EEZ'],

alpha=0.8)

plt.title("Fishing hours in front of the coast of Perú", fontsize=16)

plt.xlabel('Date', fontsize=14)

plt.ylabel('Total hours', fontsize=14)

plt.legend(loc=2, fontsize='large')

plt.show()

The orange region of the graph indicates the amount of fishing occuring in international waters, while the blue area represents the fishing that takes place within Peru’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). It is likely that this fishing is carried out by Peru’s own fleet or by other countries with which Peru has bilateral fishing agreements. From the data, it is clear that the majority of fishing effort occurs outside of Peru’s EEZ, with some instances exceeding 30,000 hours. This highlights the importance of the EEZ, as it protects Peru’s resources from being overexploited by foreign fleets. Without the EEZ, foreign fleets would be able to legally access and deplete Peru’s waters.

On the other hand, there is a distinct pattern of fishing activity that tends to peak during the summer and fall months, and decrease during the winter. This trend is consistent both inside and outside the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Additionally, it appears that there has been an increase in fishing hours when comparing the first two years of data with the last three years. However, this could be attributed to better availability of AIS data over the years rather than any actual changes in fishing patterns. Furthermore, there is no clear evidence of an influence of ENSO events on fishing activity. In fact, values for 2014 and 2015 are relatively similar, indicating that fishing hours may not be the most effective way to measure the impact of atmospheric and oceanic oscillations on fisheries.

Overall, the notebook has successfully introduced the GFW datasets and its access through GEE. However, continuing the analysis could provide further insights into the study case.

We could improve our analysis in several ways. For instance, we could investigate the contribution of different fishing flags to the total fishing effort both inside and outside the EEZ. This would allow us to identify which international fleets are fishing in Peru’s waters and evaluate the countries that have fishing agreements with Peru. We could also compare total navigation hours (a dataset also available from GEE) with fishing hours to establish how busy the waters are within our areas of interest.

Furthermore, we could delve deeper into exploring the effects of ENSO. Initially, we could have included a time series of the ENSO indicator from the 3-month mean of ERSST.v5 sea surface temperature anomalies in the Niño 3.4 region, which we did not incorporate as we did not detect any influence. In this regard, we could have explored additional GFW datasets (accessible through Google BigQuery) representing fishing activities using indicators influenced by El Niño.

The content of the present notebook can be accessed using Binder’s services for building and sharing reproducible and interactive computational environments from online repositories.

Click this link to launch the notebook in your browser:

Christensen, V., de la Puente, S., Sueiro, J. C., Steenbeek, J., & Majluf, P. (2014). Valuing seafood: The Peruvian fisheries sector. Marine Policy, 44, 302–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2013.09.022

El Niño | National Geographic Society. (n.d.). Retrieved November 29, 2022, from https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/el-nino

FAO. Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics. Global capture production 1950-2020 (FishStatJ). 2022. In: FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Division [online]. Rome. Updated 2022.

GFW (global fishing watch) daily fishing hours | Earth Engine Data catalog | google developers (no date) Google. Google. Available at: https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/GFW_GFF_V1_fishing_hours (Accessed: November 30, 2022).

Global Fishing Watch Application Programming Interfaces (API) Documentation (https://globalfishingwatch.org/our-apis/documentation#introduction)

Kroodsma, David A., Juan Mayorga, Timothy Hochberg, Nathan A. Miller, Kristina Boerder, Francesco Ferretti, Alex Wilson et al. “Tracking the global footprint of fisheries.” Science 359, no. 6378 (2018): 904-908. DOI:10.1126/science.aao5646.

@online{french2023,

author = {Jessica French},

title = {Peruvian {Fisheries} {Effort}},

date = {2023-01-10},

url = {https://jessicafrench.github.io/2023-01-09-peru-fisheries/},

langid = {en}

}